As winter's grasp loosens, the countryside around us awakens with understated signs of spring. Beyond the familiar daffodils and blackbirds, a closer look reveals nature’s more subtle cues of the season’s return. These overlooked signs—small, unassuming, yet deeply rooted in history and folklore—whisper their presence to those who take the time to notice.

One of the earliest botanical indicators of spring in the region is dog’s mercury (Mercurialis perennis), a humble green plant that flourishes in the dappled shade of ancient woodlands. Its name alone hints at its folklore—historically, it was believed to have associations with Mercury, the Roman god of communication and travel. Despite its delicate appearance, it is highly toxic to both humans and livestock, a trait that may have contributed to its mystical reputation. In the past, the presence of dog’s mercury was used to determine whether land had been continuously forested for centuries, making it a silent witness to Devon’s deep woodland history.

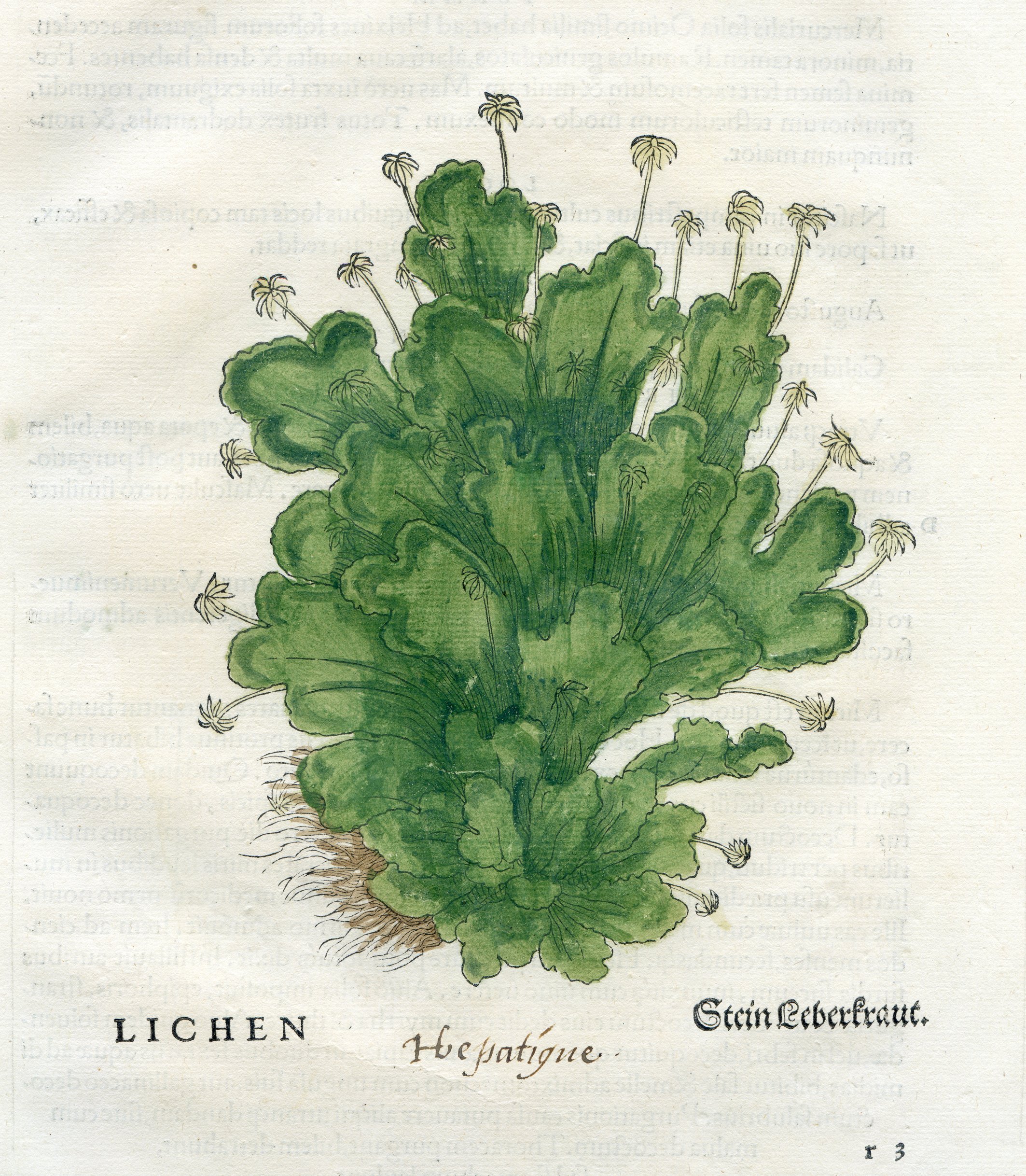

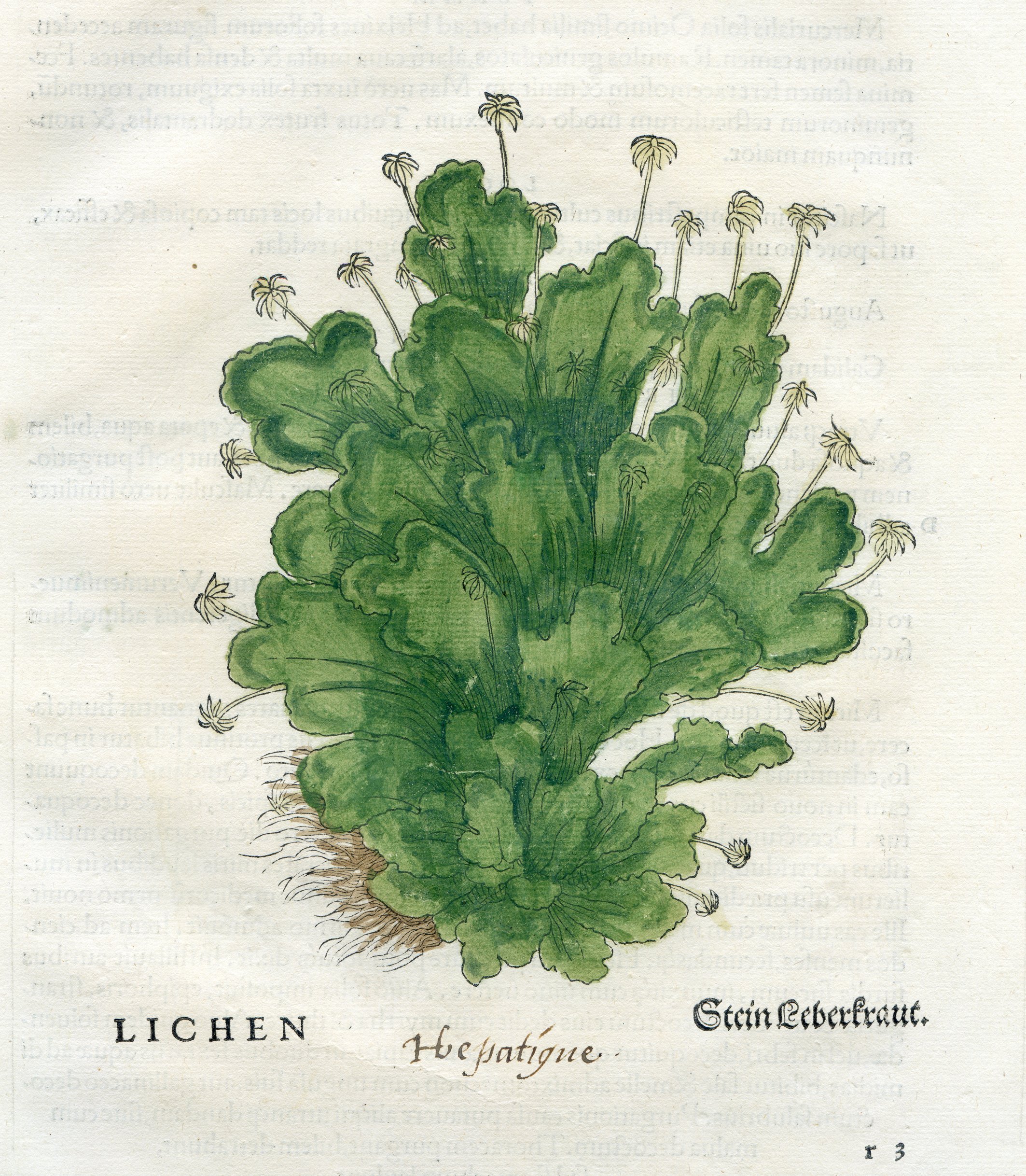

The unassuming yet ancient liverworts that cling to the damp stone walls and hedgerows of green lanes tell a different story. These primitive plants, some of the oldest life forms on Earth, have existed in one form or another for over 400 million years. Their presence is a quiet testament to the purity of the environment—these delicate organisms thrive only in clean, unpolluted air. In medieval times, liverworts were part of the Doctrine of Signatures, a belief system that held that a plant’s appearance indicated its medicinal use. Resembling a liver in texture and form, it was once used to treat liver ailments, though modern science has disproved its efficacy.

As the woodland edges stir with early birdsong, the song thrush (Turdus philomelos) begins to break the winter silence. Unlike its more boisterous cousin, the blackbird, the song thrush’s melody is intricate and repetitive, as if refining its song for the season ahead. In Victorian times, it was widely believed that thrushes could foretell the weather—if their song was particularly insistent, it was said to herald a coming storm. These birds also hold a place in British literature and poetry, notably inspiring the works of Thomas Hardy and Robert Browning, who admired the thrush’s defiant song as a symbol of hope and renewal.

Hidden within the cool waters of ponds and slow-moving streams, frogspawn makes its quiet appearance in early spring. This gelatinous mass of developing life has long been regarded as a symbol of fertility and transformation. In Celtic folklore, frogs were associated with the element of water and were believed to bring rain, making them an important figure in agricultural traditions. Their sudden appearance in spring also marked the moment when the land, long barren from winter, began to teem with life once more. Today, the presence of frogspawn is an important ecological indicator, revealing the health of local waterways and the resilience of amphibian populations.

On the first warm afternoons of the year, the buff-tailed bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) queen can be seen sluggishly emerging from her winter dormancy. Unlike the honeybee, which maintains a colony year-round, the bumblebee’s life cycle begins anew each spring, with a lone queen seeking out nectar and a suitable nest. Bees have been revered in folklore for centuries, often seen as messengers between the physical and spiritual worlds. In ancient Britain, it was customary to whisper secrets to bees, believing that they carried messages to the gods. The sight of a queen bumblebee searching for a nest is a small but vital moment in the renewal of life, as she will give rise to an entire colony of pollinators essential to the ecosystem.

On the woodland floor, the wood anemone (Anemone nemorosa) shyly unfolds its white petals, often before the trees above have fully leafed out. This delicate flower is steeped in legend—according to ancient Greek mythology, it was created from the tears of Aphrodite as she mourned the death of Adonis. In the British countryside, it is sometimes called the “windflower” because it was believed to bloom only when stirred by the breath of the wind spirits. Traditionally, it was thought to bring luck if picked before noon, though, in reality, its brief bloom is best admired in situ, as it is a key nectar source for early pollinators.

Meanwhile, Devon’s verges and stream banks become dotted with the glossy yellow flowers of lesser celandine (Ficaria verna). The poet William Wordsworth, so captivated by its bright, star-like blooms, wrote three separate poems dedicated to the flower. In folk medicine, lesser celandine was once used to treat scurvy due to its high vitamin C content, and its roots, resembling small tubers, were believed to cure haemorrhoids—hence its old name, “pilewort.” Though dismissed by modern medicine, it remains one of the first flowers to bloom in spring, its golden petals reflecting the increasing daylight and the quiet return of warmth to the land.

These overlooked signs of spring may lack the grandeur of daffodils or the fanfare of cuckoos, but they each tell a rich, storied tale of nature’s awakening. They are remnants of ancient landscapes, bearers of folklore, and silent heralds of renewal. By pausing to notice them, we gain a deeper appreciation for the quiet, intricate symphony of spring’s arrival.