Journal

Mutualism Series - The Hidden Harvest Beneath The Moor

October settles softly over the moor. Mornings arrive cool and damp; the sun rises through veils of mist that hang low over the bracken. Out among the fading heather, our Red Devon cattle graze steadily, their dark coats glowing red-brown against the tawny grasses. To the casual eye, it’s cattle, pasture, and open sky. But beneath every hoofprint lies a world of astonishing activity, a biological web as intricate as the branches of any tree. Here in the thin soil of the moor, fungi and microbes weave the foundations of life, maintaining the fertility of land that has supported livestock for centuries.

Soil is a living tissue made up of minerals, water, air, organic matter, and an unimaginable number of organisms. A teaspoon of healthy soil may contain more living things than there are people on Earth. Among these, mycorrhizal fungi are the master connectors. They colonise the roots of wildflowers and grasses, extending their filaments — called hyphae — through the soil to form an underground network that transports water and nutrients in exchange for sugars produced by photosynthesis. The plants feed the fungi; the fungi feed the plants. This partnership enhances a plant’s ability to absorb phosphorus, nitrogen, and trace elements, helping vegetation thrive even in the thin, acidic soils of the moor. Around these fungal threads live bacteria that fix nitrogen, protozoa that graze on bacteria, and micro-arthropods that shred organic matter into fragments small enough for decomposition. Each group plays its part in a microscopic economy powered by the roots above.

When the herd graze, they become a part of that subterranean cycle. Their selective feeding keeps dominant grasses in check, allowing sunlight to reach smaller herbs and wildflowers. This increased botanical diversity translates directly into fungal diversity, as each plant species hosts its own suite of symbiotic partners. The cows’ hooves press seeds into the ground and gently disturb the surface, mixing organic matter with mineral soil - a process farmers once called “the cattle plough.” Moderate trampling creates small pockets where oxygen can enter and water can accumulate, allowing various fungal species to establish. In contrast, where animals congregate too densely, the soil can compact, restricting air flow and reducing the fine pores that fungi use to explore their environment. The art of good grazing management lies in finding that balance: enough pressure to stimulate growth and microbial turnover, but not so much that the living soil suffocates.

Studies across European grasslands have begun to quantify how grazing intensity alters the underground biodiversity that sustains pasture ecosystems. One recent survey in Italian mountain meadows compared fungal communities under four grazing levels: no grazing, light, moderate, and intensive. The results tell a fascinating story. In ungrazed plots, researchers recorded around 58 fungal species, dominated by mycorrhizal fungi - the mutualists that connect plant roots to nutrients. With light grazing, total fungal richness increased slightly to 62 species, largely thanks to a rise in saprotrophic fungi, the decomposers that break down dead plant matter. Under moderate grazing, total fungal diversity dropped to 55 species, but the composition shifted: saprotrophs continued to thrive, while mycorrhizal fungi declined somewhat. In intensively grazed meadows, overall fungal richness fell sharply to 42 species, with mycorrhizal diversity nearly halved compared to ungrazed plots.

What this means is subtle but vital. A little grazing can actually enhance biodiversity - by opening up niches, stimulating decomposition, and creating a variety of microhabitats. But when grazing becomes too heavy or continuous, it disrupts the fungal networks that bind the soil and support plant nutrition. Mycorrhizal fungi, which rely on stable plant hosts and delicate hyphal structures, are especially sensitive. Their decline under intensive pressure weakens the symbiotic links that supply plants with nutrients, leading to less resilient pastures. Meanwhile, saprotrophic fungi - more opportunistic and fast-growing - increase temporarily in the churned soil, but they cannot replace the long-term benefits of the symbiotic species.

For us, these numbers translate into clear management lessons. A pasture with moderate, rotational grazing - where animals move in rhythm with the growth of vegetation -supports the broadest range of fungal life.

Grazing also alters the microclimate of the meadow. Shorter vegetation allows greater temperature swings between day and night and increases evaporation at the surface. Some fungi thrive under these variable conditions - especially thermotolerant species capable of surviving brief dry spells - while others retreat deeper into the soil where moisture remains. Research from alpine and temperate grasslands shows that grazed plots can be two to three degrees warmer by day and slightly cooler by night than ungrazed areas. This subtle shift in temperature range alters which fungi dominate: communities become more dynamic, turning over rapidly as conditions change. The result is a mosaic of niches - miniature worlds of warmth, moisture, and texture - that together build resilience into the soil ecosystem.

Where there are grazing animals, there is waste, and in ecological terms, manure is a gift. Each pat is a concentrated pulse of organic matter that fuels decomposer fungi and bacteria. These so-called coprophilous fungi are specialists: some can survive the journey through an animal’s digestive tract, their spores lying dormant until they emerge in fresh waste. Within hours of deposition, simple sugar-loving yeasts appear, followed by filamentous ascomycetes that digest cellulose and hemicellulose, and finally by basidiomycetes able to break down lignin - the toughest component of plant cell walls. Over a few weeks, the pat collapses back into the soil, its nutrients reincorporated into the root zone. Earthworms drag fragments underground, microbes mineralise the remains, and once again the mycorrhizal fungi deliver those nutrients to living plants. In this way, the cattle feed the fungi as much as the fungi feed the plants that feed the cattle.

Over time, grazing alters which plant species dominate, and that in turn reshapes the fungal community. Palatable plants are eaten more often, giving space to tougher herbs or thorny species. Because mycorrhizal fungi are often host-specific, a change in vegetation composition means a change in fungal partners. Light to moderate grazing tends to increase total fungal diversity by creating spatial heterogeneity - patches of cropped grass beside taller tufts and flowering herbs. But when grazing becomes too intense or continuous, many sensitive fungi disappear, replaced by a handful of generalists adapted to disturbance. The difference is visible above ground too: the richest, most colourful meadows with waxcap mushrooms, clovers, and orchids are almost always those managed under traditional, low-intensity grazing regimes where the land is given time to rest and recover.

The influence of these fungal and microbial processes reaches far beyond ecology; it shapes the very flavour and nutrition of what we produce. Fungi enhance the mineral content of forage by improving nutrient uptake from soil particles otherwise inaccessible to roots. Studies comparing grazed and ungrazed pastures show that herbage from grazed land often contains higher levels of protein, potassium, and iron - a reflection of the soil’s active nutrient cycling. Our Red Devons, feeding on these fungal-enriched plants, incorporate that vitality into their own tissues. The quality of the beef - its depth of taste, the subtle complexity that marks species-rich grass-fed meat - begins with the microbial health of the soil. Every mouthful the cattle take is a conversion of sunlight and symbiosis into sustenance.

Sustaining this balance requires mindful management. Rotational or seasonal grazing, practised by Bella and Toby, gives pastures time to recover and allows fungal networks to rebuild after disturbance. Maintaining areas of ungrazed refuge - along hedgerows, in corners of the moor - supports the persistence of delicate species that might otherwise vanish. Where rest periods are honoured, we often see a rebound in waxcaps and other indicator fungi whose presence signals healthy, undisturbed grassland. These visible fruiting bodies are the messengers of an invisible abundance below.

When the herd finally returns from the moor to the Mill Barton pastures later this season, they bring with them the benefits of that living soil: a strengthened microbial gut from diverse forage, minerals gathered through fungal pathways. In turn, their manure will seed our lower fields with spores and microbes from the moor, continuing the exchange between landscapes. It is a dialogue measured not in words but in cycles of growth and decay, in hoofprints and hyphae, in the quiet chemistry of life beneath our feet.

To observe the herd on an autumn afternoon is to witness mutualism made visible - not as an abstract concept, but as the everyday functioning of an ecosystem. The cattle depend on the grasses, the grasses on the fungi, the fungi on the carbon from the plants, and all depend on the careful hand that keeps balance between them. The system’s strength lies in its reciprocity. What we give to the land in rest, diversity, and respect, it returns to us in fertility, flavour, and the well-being of our herd. The fungal networks continue their silent work - binding soil, feeding roots, and reminding us of the powerful underworld that lies beneath.

A Team Trip to Glen Falloch and Ben Lawers

Earlier this month, we traded the rolling fields of Mid Devon for the dramatic peaks and glens of Glen Falloch in the South West Highlands. It was a week of connection, discovery, creativity and conservation - and a fair bit of tick-wrangling.

Glen Falloch is also part of our restoration work. In collaboration with Glen Falloch Estate and Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park, we’re pioneering innovative approaches to restoring biodiversity, reviving ecologically functional grasslands and reconnecting fragmented patches of ancient upland forest.

Set against a backdrop of misty hills, cascading waterfalls and tumbling burns, Glen Falloch gave us all the chance to slow down and reconnect. We covered miles on foot, ate well, gathered around the fire in the evenings, sipping more than our fair share of whisky and tea. Toby landed a trout so big it now has mythical status, and the air was filled with laughter, good conversation (and midges).

One of the most memorable moments for the team? Painting sessions on the hillside. Inspired by the landscape around us - its shifting light, textures and silence - we spent hours in the evening after work painting en plein air. It was grounding, creative and meditative. That is, until we realised we were sitting on top of Tick Mountain. Nature giveth and nature taketh away.

A highlight of our trip was our guided tour of Ben Lawers National Nature Reserve with the brilliant Helen Cole, Property Manager for the National Trust for Scotland. Her passion for the land is infectious, and the work her team is doing, alongside local farmers Maj and Peter McDiarmid, is both innovative and inspiring. Nestled above Loch Tay, this National Reserve is home to one of the UK’s rarest alpine and arctic flora, many of which we were lucky enough to see up close.

We spotted alpine saw-wort (Saussurea nuda), with its soft purple blooms, and the delicate Purple mountain saxifrage (Saxifraga oppositifolia), clinging to rocky outcrops like living jewels. Dwarf willow (Salix herbacea) and woolly willow (Salix lanata), both scarce and slow-growing, peeked through the grass and scree. Helen Cole, our guide for the day, helped us identify these resilient plants and explained the delicate balance they depend on - a balance now being actively restored by the reintroduction of cattle.

It wasn’t just the plants that impressed us. The hillside echoed with the calls of red grouse, and we caught glimpses of garden warblers (Sylvia borin), willow warblers (Phylloscopus trochilus) and managed to film a small-pearl bordered fritillary (Boloria selene).

Small-Pearl Bordered Fritillary

Stepping out of our usual rhythms and into the wild Highland landscape, we witnessed firsthand how thoughtful, collaborative land management can reverse centuries of ecological decline and help fragile habitats thrive again.

We painted, we walked, we talked deeply and laughed often. Spotted rare plants and stood quietly among the mountain willows older than many of us.

A heartfelt thank you to Helen Coles and the team at Ben Lawers for your time, insight, and inspiration. We left inspired, a bit itchy, carrying a renewed sense of connection to a different landscape and restoring the world around us.

The Marvel of Migration

The Arrival of Migratory Birds

Every spring, the skies over the UK are filled with life in motion—millions of birds navigating incredible distances with astonishing precision. Here at Mill Barton, we spend lunchtime in April and May observing the skies for the dances and songs of swallows, swifts and cuckoos. And every year, as they carve arcs through the sky, we find ourselves asking:

Why do they come and go?

How do they endure such perilous journeys?

And most wondrous of all—how do they know the way?

Why Do Birds Migrate?

At the heart of migration is one simple thing: survival. Birds migrate to take advantage of seasonal abundance and to avoid scarcity.

Food: Insects, seeds, and nectar—the staples of many birds—disappear during the UK winter. Heading south means a banquet of sustenance in warmer climates.

Breeding: Many birds migrate to the UK in spring because of its long daylight hours, which allow extra time for feeding hungry chicks. Plus, there's often less competition for territory.

Climate: For many species, avoiding harsh winters is crucial. Cold weather not only limits food but also increases energy demands.

Migration is a high-risk strategy, but the payoff—successful breeding and better survival rates—makes it worthwhile for many species.

How Do Birds Migrate?

Birds migrate using a variety of impressive adaptations. Before migration, birds go into hyperphagia - eating excessively to build fat, their primary fuel for the journey. Then, using their long, narrow wings in species like swallows allows efficient long-distance travel. Some birds, like swifts, use specialised flight techniques, meaning they can sleep while gliding.

Birds follow ancient flyways—established paths that typically avoid large ecological barriers like mountains or oceans, unless necessary. Some fly bravely across the Sahara, facing ruthless sandstorms and the deadly Sirocco (a strong Mediterranean wind) - a journey of about 6000 miles which they usually complete in less than two weeks.

How do they know where to go?

Birds use a sophisticated multi-sensory toolkit -

Magnetoreception: Species like the European robin are thought to "see" Earth’s magnetic field, guiding them even in the dark.

Celestial navigation: Many birds migrate at night, using stars and the moon to orient themselves.

Inherited memory: Some birds are born with internal maps encoded in their genes, while others learn routes from their parents.

But what happens when the world they migrate through changes?

Climate Change and the Limits of Adaptation

As Earth’s climate changes, migratory birds face an existential test: Can they adapt quickly enough?

Groundbreaking research from the Bird Genoscape Project at UCLA is offering a window into that question. In their most recent study, published in Science, researchers studied the yellow warbler—a species not found in the UK, but one that migrates similarly across vast regions of North America.

Here’s what they found:

Using DNA from over 200 birds across its breeding range, scientists identified climate-related genes—suggesting certain populations are genetically adapting to local environmental conditions.

Alarmingly, the populations that most need to adapt due to climate stress are already in decline.

Some groups had genetic-environment mismatches, meaning their DNA isn’t keeping pace with rapid environmental shifts.

These insights have powerful implications for UK species too. Evolutionary biologist Kristen Ruegg, co-director of the Bird Genoscape Project, said this work gives us a genetic map of which populations are at greatest risk, allowing conservationists to act before it's too late.

Let’s spotlight some of Britain’s most iconic migrants:

Barn Swallow (Hirundo rustica)

Fork-tailed, glinting in sunlight, darting and gliding with effortless grace—the swallows return. Though they travel thousands of miles—from the southern reaches of Africa to the fields of Devon or the rafters of a Yorkshire barn—swallows are fiercely loyal to place. Many return to the very building or beam where they first hatched. Year after year, they stitch their mud-cup nests into the fabric of human life, coexisting with us in a rare harmony. As aerial insectivores, swallows play a crucial role in controlling fly and mosquito populations, serving as natural pest control across rural and suburban landscapes throughout the summer here in the UK. Their departure each autumn is felt just as keenly as their arrival in the spring—a farewell not just to warmth and light, but to something more intangible: the rhythm and reliability of nature.

Common Cuckoo (Cuculus Canorus)

The common cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) is a voice of the British spring, arriving from Africa each April, crossing thousands of miles to breed. Known for its haunting two-note call and its unusual strategy of laying eggs in other birds’ nests, the cuckoo is a brood parasite—its young raised by reed warblers, dunnocks, or meadow pipits, often at the cost of the host’s own chicks.

This behaviour, while stark, weaves the cuckoo tightly into the web of life. Its survival depends on the timing of insect emergence, healthy habitats, and the fate of its host species—making it a living signal of ecological change. Cuckoo numbers have dropped sharply, reflecting declines in caterpillars, nesting grounds, and climate stability.

To protect the cuckoo is to protect much more: the insects it feeds on, the birds it relies on, and the balance of ecosystems it silently measures. Its voice may be fading, but it still tells us what the land is losing.

Common Swift (Apus Apus)

The common swift (Apus apus) arrives in the UK each May, slicing through summer skies after a journey from Africa. For just a few months, they fill the air with their calls and consume thousands of flying insects daily—midges, flies, mosquitoes—quietly keeping ecosystems in balance.

Swifts live almost entirely in the sky. They eat, drink, sleep, and even mate on the wing. A young swift may stay airborne for three years before it ever touches down. Though often mistaken for swallows, they belong to a different lineage, built for life in motion.

They nest in crevices of old buildings, making them especially vulnerable to modern renovations that seal away their homes. Since the 1990s, their numbers have dropped by over 60% in the UK. Loss of nesting sites and insect decline are driving this silent fall.

Now Red-listed, swifts are a signal of change in our towns and cities. Protecting them means keeping space in our architecture, letting insects thrive, and listening to what their vanishing flight is telling us about the health of the world below.

Why Migratory Birds Matter Now More Than Ever

Migratory birds like swallows, cuckoos, and swifts are more than fleeting signs of British summer—they are essential to the ecological rhythm of the UK. These species consume huge numbers of flying insects, naturally controlling pests that affect crops, gardens, and public health. Their arrival each spring marks the seasonal renewal of life and signals that the countryside, farmland, and even our towns still support functioning ecosystems.

But across the UK, these familiar birds are disappearing. Cuckoo numbers in England have dropped by over 65% since the 1980s; swift populations have declined by more than 60% since the 1990s. Climate change is shifting the timing of migrations, reducing the availability of insect prey, and pushing birds to arrive too early or too late. At the same time, habitat loss—from sealed rooflines to insect-poor landscapes—continues to chip away at their ability to breed and feed.

These species don’t just cross continents—they connect us to a wider world. Their survival depends on healthy ecosystems stretching from sub-Saharan Africa to the UK’s hedgerows, wetlands, and rooftops. When they decline, it’s a signal of something larger: that our insect populations are collapsing, our landscapes are becoming sterile, and our seasons are falling out of sync.

Protecting migratory birds in Britain means restoring insect-rich habitats, preserving nesting sites in old buildings, limiting pesticide use, and backing international efforts across migratory routes. These birds are part of our natural heritage, our folklore, and our future. If they vanish, it’s not just their absence we’ll feel—it’s the weakening of the systems that support all life here, including our own.

Restoring Atlantic Temperate Rainforests - A Lesson From The Salmon Forests of Canada

It has been fascinating to stumble into the world of rainforest restoration in the UK, at what feels like a very pivotal time for cultural identity; as the lichen and fern-clad, rain-sodden woodlands of coastal UK are increasingly being reimagined as Atlantic Temperate Rainforests. Having moved over from Vancouver Island, Canada, I’ll admit that the last thing I expected to encounter in the UK was rainforest. Rather, I had pictured wind-battered coastal cliffs, rolling meadows with the occasional craggy old oak, and Heathcliffe emerging from the mist of a heather-clad moorland.

I had been in the vicinity of rainforest restoration for some time in Canada, where I learnt of incredible work being done by Coastal First Nations and organisations such as Reddfish Restoration. This work was being carried out throughout Nuu-Chah-Nulth territories on the West Coast of Vancouver Island. One key thing that stood out for me on the Island was the focus on restoring ecosystems at scale. In these ‘salmon forests’, it seems that one of the most crucial elements for rainforest integrity is river and intertidal restoration, and vice-versa. In the forests of the Pacific Northwest, the connection between ocean and rainforest, maintained through the thread of the river, forms the backbone of these vital habitats. So, restoration of any one habitat really must focus on them all. To illustrate this, studies have found that marine-derived nitrogen is transported hundreds of kilometres upstream in the bodies of the salmon, where bald eagles, bears, and wolves transport this vital nutrition further into the forest and even high up into the tree canopy.

Back on this side of the Atlantic, when I hear these conversations about stewarding, enhancing, and expanding the fragmented and vital Atlantic temperate rainforests, I can’t help but be struck with the feeling that the thread of how vital our rivers and coasts are to rainforests is missing, or at least underrepresented, from the conversation over here. The state of Atlantic Salmon, a distant relative of the Pacific Salmon, is dire. Now listed as endangered in the UK, populations are in crisis and have declined 70% in the last 25 years, with returns of just 50 fish counted on the River Dart in 2023, for example, according to the Fishtek Totnes Weir.

But what to do about our Salmon? Well, perhaps a good place to start is to think about the linkages between the rainforests that line the river valleys of salmon runs to the river themselves, and in turn their ocean-going fish. The question in my mind is how we can better manage our rivers, crucial riparian arteries between land and sea, alongside their linked rainforest habitat,s with our critically endangered Atlantic salmon in mind?

This past week, I was lucky to snag a spot at a Rainforest Management Day offered by the Woodland Trust in partnership with Plantlife and Natural England at Yarner Wood in East Dartmoor.

We saw an incredible example of this sort of riparian-based rainforest management playing out at Yarner Wood. The felling works that have been done have created biogenic (any natural feature that helps to slow the flow of water, such as woody debris) interventions to help slow and spread the flow of the river coursing through the site.

Salmon require cool, clean, oxygen-rich fast-flowing water with extensive gravel beds to spawn in. They are very vulnerable to changes in river water quality, temperature, and flow. By adding woody debris into the watercourse at Yarner Wood, sediment is caught and filtered, thereby improving water clarity and quality. Gravel is also trapped and filtered which optimises the rivers for salmon, as they require larger, smooth cobbles for spawning.

The next step, we’re told by The Woodland Trust team, will be to plant willow along the river bank, helping to provide appropriate shading to keep river temperatures optimal for salmon. Water temperatures beyond 16°C may result in salmon run declines; as warming temperatures cause salmon to become stressed and unable to spawn, and eggs also cannot persist in higher temperatures. Alongside providing shading, the saturated, humid sponginess of intact, functional temperate rainforests helps to moderate humidity and in turn, helps to optimise salmon stream temperatures. In addition to temperature regulation, riparian willow planting will also help to stabilise river banks thereby supporting runoff mitigation, and will also gradually add more biogenic woody material from the willow into the mix.

Overall, this filtering, slowing of flow, and re-connecting of rivers with their floodplains also provides the invaluable benefit of flood control for downstream communities and increases the resilience not only of the rainforests but the people around them.

At the event, we learned from Sam Manning at the Woodland Trust that the three key components for functional temperate rainforests are good air quality (which bryophytes - lichen, mosses and liverworts rely on), light reaching through a somewhat open canopy (which bryophytes also require to photosynthesise), and ample water and rainfall to create appropriate humidity level within rainforests. The water bit is key. Centuries of drainage have removed and rearranged the way water flows through the land and have resulted in drier habitats, including our rainforests. Therefore, the key to restoring rainforest function is rewetting them; removing drainage, the addition of biogenic material, and allowing water to flow freely across floodplains, all to help raise the water table. This moistening of the whole forest has benefits not only for humidity regulation but also for the control of over-dominant plants such as bracken, which thrive in drier soils and don’t like soggy feet.

So as we manage rainforests, it becomes clear that a huge focus area should also be on managing water. Slowing, spreading, sinking it into the land, rewetting our woodlands, and thinking about managing riparian integrity will have cascading positive effects down to the coast. Where our beautiful Atlantic Salmon will join the rainforest story and help replenish upland habitats through their life cycle. Perhaps restoring a small patch of Atlantic temperate rainforest, in turn, can help strengthen the connections and integrity of an entire coastal ecosystem.

I would like to extend a huge thank you to the Woodland Trust, Plantlife, and Natural England teams for hosting everyone at Yarner Wood. As well, a huge shoutout to the tree works team that carried out the interventions on the ground at the event, based on the Rapid Rainforest Assessment results.

These works, such as thinning, coppicing, and bark-ringing will help open up the canopy, create standing deadwood, and diversify the dominance of single-age oak coppice currently present at Yarner. It was inspiring to see this work, alongside river restoration, playing out to ultimately encourage a more dynamic and resilient rainforest at Yarner Wood.

Woodland Trust Rainforest Recovery Website

In Season, In Place - Rediscovering What The Land Once Gave Us

For centuries, the people of Devon and Cornwall thrived on a diet shaped by their land and sea. From the Cornish Earlies, dug fresh from the rich soils of Cornwall, to the Mazzard cherries that once flourished in North Devon Orchards, the region's food reflected its heritage. Cider culture, too, was deeply ingrained in local life, with orchards covering the countryside, producing the sharp and sweet varieties that sustained generations. And then there were the humbler staples—swedes, pilchards, barley bread—once the backbone of working-class diets.

Yet today, much of this history is slipping away. Supermarkets offer instant satisfaction, with year-round produce sourced from thousands of miles away. Fast food and convenience meals have replaced the slow, seasonal rhythms that once dictated what we ate and when. The result? A disconnect from our heritage and the seasonal way of living.

South West Origins

The Cornish Early potato has been cultivated in the mild climate of Cornwall since at least the mid-1700s. Originally grown as a staple alongside pilchards, it wasn’t until the early 19th century that Cornish Earlies became a prized commodity. By 1808, they were being shipped across the UK, Europe, and even as far as Barbados and Newfoundland. Their unique taste, shaped by the coastal air and sandy soil, made them unlike any other potato—yet today, they are at risk of being forgotten in favour of mass-produced, uniform varieties.

A successful crop of Cornish Earlies grown using Hadfield Special Potato Manure, St Germans, Cornwall, circa 1910’s

The Decline of Cider Culture

Cider-making has been at the heart of Devon and Cornwall’s identity for centuries. Orchards filled with traditional apple varieties like Kingston Black, Dabinett, and Slack-ma-Girdle once produced rich, complex ciders that aged like fine wine. These weren’t just drinks—they were part of local ritual, culture, and community. But the rise of industrial cider-making has led to the dominance of mass-produced, sugar-laden alternatives. Small-scale cider makers are fighting to keep the tradition alive, but without consumer support, the unique, heritage ciders of the Southwest risk becoming nothing more than a nostalgic memory.

The Cider Works, originally built in 1935 for The Creedy Valley Cider Company, Crediton, Devon

Swedes, Barley, and the Lost Staples

Swedes, often associated with harsh winters and frugal cooking, were a mainstay in Cornish and Devonian kitchens. Alongside barley bread, they formed the foundation of many traditional dishes, from Cornish pasties to hearty stews. Oats, too, were a staple grain grown across Dartmoor and used in everything from oatcakes to slow-cooked porridge. And in wetter soils, rye and even Devon White Wheat—an old variety known for its nutty depth—thrived until industrial agriculture pushed them aside.

Today, these simple, nutritious foods are often overlooked, replaced by imported alternatives that bear little connection to the land and the people who once depended on them.

Coastal Foraging and the Ocean’s Pantry

Beyond farmland, the coastline offered another layer of seasonal food wisdom. Sea beet and samphire once filled pots and pans with salty brightness. Laver, a mineral-rich seaweed, was foraged from tidal rocks and stewed into laverbread. Shellfish like limpets and periwinkles were gathered from rock pools and served with vinegar or stewed in fish broths—humble, nourishing, and deeply rooted in place.

These wild foods weren’t delicacies. They were dinner. And their availability followed nature’s tide.

Mazzard Cherries: North Devon’s Lost Treasure

The mazzard or gean is a domesticated form of wild cherry (Prunus avium). In years gone by, they were widely grown in North Devon, particularly in the villages of Landkey, Swimbridge, and Goodleigh, where the trees thrived on the slopes of the Taw Valley in the damp, mild climate.

Mazzards were taken to the Pannier Market in Barnstaple and sold by the pound. It is said that in 1645, the future King Charles II sampled mazzard pie when he stayed with the Countess of Bath at Tawstock. Mazzards are gently cooked and served with Devonshire clotted cream or made into tarts or pies. As the 20th century progressed, mazzards fell out of fashion due to the substantial amount of labour required to protect and harvest the crop. After 1918, rural depopulation led to a decline in available pickers, making mazzard growing unviable.

Mazzard trees grow very tall, and farmers built long ladders to reach the top. There are five known strains of mazzard: Dun, Greenstem Black, Black Bottler, Small Black, and Hannaford. Landkey was also home to three varieties of indigenous apples: Stockbearer, Limberland, and Listener. Another special fruit tree from the area was the Landkey Yellow, a type of plum commonly used in hedgerows.

Prunus Avium, Mazzard Cherry Tree

Bringing Back Seasonal Eating: Listening to Nature’s Calendar

As well as becoming disconnected from our past and heritage, we have managed to miss the important vitamins and nutritious values that the land presents to us throughout the year. Think about it: in spring, just like us, everything starts to wake up and come out of hibernation. Then with the help of Mother Nature, we’re gifted exactly what our bodies need.

Take wild garlic, for example—abundant from late March through to May. Wild garlic has been traditionally used for its medicinal properties for centuries. It is known to have antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral properties, and may help lower blood pressure and cholesterol levels. It also supports digestion, boosts the immune system, and has anti-inflammatory effects. Rich in vitamins A and C, iron, magnesium, and manganese, it’s a perfect spring tonic.

Later in the year, elderberries ripen between August and October, ready to be turned into cough syrup or cold-preventing tinctures for winter. We often search far and wide for medicinal properties, sometimes from the other side of the world, when what we need is already on our doorstep. Nature is shouting at us to come back to our roots. She’s reassuring us that most of what we seek nutritionally is already here, in the soil and hedgerows of our native land.

Of course, for city folk, it's a different story. But that doesn’t mean you can’t be conscious. Even in supermarkets, pause for a moment. Ask yourself: what’s in season right now? How can I reduce the air miles of the food I eat? What impact is the harvest of this particular fruit or vegetable having on the environment?

When we eat seasonally, we're not just eating with the land—we're syncing with the ancient intelligence of our bodies. This isn’t romantic nostalgia. It’s biological design.

How We Find Our Way Back

Reviving these traditions doesn't mean turning back the clock—it means making conscious choices. Choosing a swede grown in Devon over a sweet potato flown in from Peru. Buying cider from a local orchard rather than a supermarket chain. Supporting farmers markets and small-scale growers instead of defaulting to big-box convenience.

Look out for Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) boxes in your area or local farm shops offering weekly veg boxes.

Visit local Pannier Markets like those in Tiverton or Crediton, if you’re based in Mid Devon.

Support heritage fruit projects like the North Devon Mazzard Heritage Orchard.

Discover wild foods—many local foragers now run courses on seasonal plants and there are plenty in the South West.

“The ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops but the cultivation and perfection of human beings.” - Masanobu Fukuoka

Uncharismatic Species - The Unsung Heroes of Our Ecosystems

When we consider wildlife conservation in the UK, we often focus on charismatic creatures like beavers, roe deer or eagles. But what about the smaller, overlooked species that quietly sustain our ecosystems? These uncharismatic species may not be in the limelight, but their environmental contributions are essential.

Below, we’ll explore some underappreciated species native to the UK and uncover the vital roles they play in maintaining ecological balance.

Black Garden Ant (Lasius niger) - Nature’s Tiny Soil Engineers

A bustling colony of black garden ants is more than just a summer spectacle towards the fruit bowl; it’s a natural force that quietly enriches the earth beneath our feet. As these industrious insects tunnel through the soil, they aerate it, improving water infiltration and nutrient circulation, which enhances plant health. Beyond their underground work, they help break down organic matter, turning dead insects and plant material into rich nutrients that nourish the land. By preying on small pests like aphids, they act as tiny guardians of gardens and crops, reducing the need for chemical pesticides.

How to Support The Black Garden Ant :

Ditch the pesticides – Chemical treatments can wipe out ant colonies and disrupt the delicate soil ecosystem.

Encourage wild spaces – Letting areas of your garden remain untamed provides safe havens for ants to thrive.

Appreciate their role – Instead of seeing ants as invaders, recognise their contributions to a healthy environment.

House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) - The Declining Urban Companion

Once a cheerful presence in bustling cities and quiet villages alike, house sparrows are now disappearing at an alarming rate. Since 1970, the UK population has plummeted by over 30 million due to habitat destruction, pollution, and the loss of natural food sources. These charming little birds play a vital role in urban and rural ecosystems, feeding on aphids, caterpillars, and other insects that damage crops and gardens. Their seed consumption also helps with plant regeneration, making them silent stewards of biodiversity. As indicators of environmental health, a drop in sparrow numbers is often a warning sign of declining air quality and urban greening.

How We Can Protect The House Sparrow :

Plant native trees and shrubs to provide shelter and nesting sites.

Avoid excessive use of insecticides that eliminate their natural food sources.

Set up bird feeders with seeds, especially in urban areas where natural food is scarce.

Marsh Spider (Dolomedes fimbriatus) - The Silent Water Hunter

Gliding across the still waters of marshes and fens, the marsh spider is an agile predator, keeping insect populations in balance. Found in wetland habitats, this semi-aquatic spider preys on dragonfly larvae, pond skaters, and even small vertebrates like fish and tadpoles. It serves a crucial role in the food chain, providing sustenance for birds, amphibians, and larger insects. The presence of marsh spiders is a strong indicator of a healthy wetland environment, as they thrive only in unpolluted waters with abundant prey.

How We Can Protect The Marsh Spider :

Preserve wetland habitats, as they are crucial for marsh spiders and many other species.

Avoid excessive pesticide use, which can disrupt insect populations and impact the spider’s food sources.

Change perceptions – Rather than fearing spiders recognise their vital role in nature.

Grey-Carpet Moth (Lithostege griseata) - The Nighttime Pollinator

While butterflies bask in the spotlight, moths work quietly through the night, pollinating flowers that bloom after dusk. The grey-carpet moth, a small but important species, plays a key role in supporting plant life, particularly in East Anglia and parts of West Wales. As it flits from bloom to bloom, it ensures that nocturnal plants, such as evening primrose, can reproduce. Moths also serve as an essential food source for bats, birds, and other nighttime predators. Alarmingly, their decline signals issues like habitat destruction and pollution, threatening the delicate balance of ecosystems.

How We Can Protect The Grey-Carpet Moth :

Reduce artificial lighting at night, as it can disorient moths and interfere with their natural behaviours along with other nocturnal species.

Plant native flowers that bloom at night provide food sources, like Evening Primrose - the yellow silken blooms of the flower open to release their scent as the sun goes down attracting the moths to an eventide aroma.

Limit pesticide use – Chemicals kill caterpillars and adult moths, disrupting their lifecycle.

Common Toad (Bufo bufo) - The Keystone Slug Patrol

With their warty skin and slow, deliberate movements, common toads may not seem like heroes, but they play a crucial role in maintaining balanced ecosystems. These nocturnal hunters feast on slugs, snails, and insects, making them a gardener’s best friend. Without toads, these pests can quickly overrun gardens and farmlands, damaging crops and flowers. As a keystone species, their presence or absence reflects the overall health of an ecosystem. Toads also serve as prey for birds and snakes, connecting them to the broader food web. However, habitat destruction, pollution, and road traffic during migration threaten their numbers.

How We Can Protect The Common Toad :

Avoid using slug pellets and pesticides.

You can also support the common toad by leaving part of your garden to grow wild, giving toads somewhere safe to hibernate and overwinter.

Be well aware of them migrating across roads to mate during the spring.

Create small ponds or damp hiding spots in gardens to shelter them.

Preserve natural habitats, especially woodlands and wetlands, where toads thrive.

Carrion Beetle (Nicrophorus silphidae) – Nature’s Cleanup Crew

Despite their eerie-sounding name, carrion beetles are vital recyclers, breaking down dead animals and returning nutrients to the soil. Without them (40% of the UK’s insects are beetles), carcasses would take far longer to decompose, increasing the risk of disease spread. Some species even bury small carcasses, fertilising the ground and creating a nurturing space for their larvae. Alarmingly, habitat destruction threatens these unsung environmental custodians.

How We Can Protect The Carrion Beetle :

Protect forests and natural landscapes where carrion beetles perform their ecological roles.

Educate others about their importance instead of viewing them as scavengers.

Reduce habitat destruction and fragmentation, as they rely on undisturbed areas for survival.

Earthworms (Lumbricus terrestris) – The Underground Engineers

Beneath our feet, earthworms perform an invaluable service, aerating the soil and transforming organic material into nutrient-rich compost. Their castings, or waste, serve as natural fertilisers that enhance plant growth. Without earthworms, the soil would become compacted and less hospitable to plant roots, affecting everything from backyard gardens to large-scale agriculture. However, intensive farming, chemical fertilisers, and over-tilling are threatening their populations.

How We Can Protect The Earthworm :

Avoid over-tilling soil, as it can destroy their burrows and habitat.

Reduce the use of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides, which can harm worm populations.

Support organic farming and gardening practices that encourage healthy soil ecosystems.

Seagulls – The Adaptable Guardians of the Coast

Often seen soaring over the sea or scavenging along shorelines, seagulls are among the most misunderstood birds. These highly intelligent and adaptable creatures play a crucial role in coastal and urban ecosystems. Seagulls move nutrients between land and sea. Their droppings (guano) are rich in nitrogen and phosphorus, which fertilise coastal plants, benefiting dune vegetation, marshlands, and seabird nesting sites. Seagulls are also skilled hunters, feeding on fish, crustaceans, and insects, keeping local populations in balance.

Seagulls are excellent problem-solvers, capable of using tools, recognising human behaviours, and even working together to access food. Their ability to thrive in both wild and urban environments has led to their reputation as opportunistic birds, but their presence is essential for maintaining ecological stability. Unfortunately, seagulls face increasing threats from habitat destruction, pollution, and food shortages due to overfishing.

How We Can Protect The Seagull :

Avoid littering – Plastic waste and discarded fishing gear pose serious threats to seagulls and marine life.

Respect their natural diet – Feeding seagulls processed food can harm their health and encourage dependency on human sources.

Protect nesting sites – Coastal development and human disturbance can disrupt breeding colonies.

Advocate for sustainable fishing – Overfishing depletes the gulls’ natural food sources, forcing them to scavenge in urban areas.

From the industrious black garden ant to the adaptable seagull, each of these species plays a crucial role in maintaining the delicate balance of Britain’s natural ecosystems. Whether found in our gardens, woodlands, wetlands, or coastal areas, these creatures contribute to the health of our environment—pollinating plants, controlling pests, enriching the soil, dispersing seeds, and keeping ecosystems in check. They are the silent workforce that supports the lush landscapes, thriving wildlife, and agricultural stability that Britain relies upon.

However, British biodiversity is under threat. Habitat loss, pollution, climate change, and urban expansion have led to declines in once-common species like house sparrows and common toads. The overuse of pesticides and disruption of natural food chains further endanger the balance that has sustained these species for centuries. Without them, the resilience of our woodlands, farmlands, and coastal environments could begin to unravel.

Protecting British wildlife starts with small changes—allowing wild spaces to flourish in our gardens, reducing chemical use, preserving natural habitats, and educating others on the importance of these creatures. By valuing the role of ants in soil health, sparrows in pest control, or even seagulls in waste management, we can shift our perception and ensure these species continue to thrive.

Britain’s biodiversity is not just a backdrop to our lives—it is the foundation of a healthy and balanced environment, something we should all be fighting for.

Laying the Land - The Vital Role of Hedgerows

A still, clement February morning, the whisper of branches being laid, the scent of woodsmoke from the Digg & Co. Studio curling through the crisp countryside air —hedge-laying is as much an art as it is a necessity. In the heart of the English countryside, hedgelayers have been quietly shaping the land for centuries, their craft ensuring that these living boundaries continue to thrive.

At Digg & Co., our team recently took part in this age-old practice, reconnecting with the land in a deeply meaningful way. Hedgelaying is more than just a rural tradition; it’s a vital force in farming, conservation, and climate resilience. In this blog, we’ll explore why it matters and why these living threads should never be left to unravel.

Hedgelaying is an ancient craft, one that has helped shape Britain’s patchwork landscape for over a thousand years. The oldest surviving hedgerow in England to date is thought to be Judith's Hedge in Cambridgeshire, which is reputed to be over 900 years old. Originally developed as a practical method for containing livestock and marking boundaries, hedge-laying ensured that hedgerows remained dense and healthy.

Each region in the UK has developed its style, reflecting the land it serves. The Midland style, with its clean-cut stems, keeps cattle at bay, while the Devon style, tightly woven and stock-proof, provides extra sturdiness against the elements. These techniques passed down through generations, remind us that hedgerows are not static features of the countryside but dynamic, evolving elements shaped by human hands.

A Haven for Wildlife

Hedgerows are among the richest habitats in the British landscape, supporting over 2,000 species, from nesting birds and small mammals to bees and butterflies. In an era of biodiversity decline, a well-laid hedge is more important than ever.

By cutting and partially bending stems, hedge-laying stimulates fresh growth, creating dense, intertwined branches that offer better shelter and food sources. Birds like Robins (Erithacus rubecula) and Bullfinches (Pyrrhula pyrrhul) find nesting sites in the thick cover, Gatekeeper Butterflies rely on grasses at the hedge base for their caterpillars and nectar from hedge flowers for adults, while dormice and hedgehogs use them as corridors, safely navigating the countryside. Without proper management, hedges grow thin and gappy, reducing their ability to support this extraordinary diversity of life.

Autumn Hedgerow, Cornwall by Amanda Hoskin

Hedgelaying and Sustainable Farming

Beyond wildlife conservation, hedge-laying plays a crucial role in sustainable farming. Hedges act as natural windbreaks, reducing soil erosion and protecting crops. They provide shade and shelter for livestock, helping them conserve energy during harsh weather.

Hedgerows also support natural pest control by attracting beneficial insects and birds that feed on crop-damaging pests. Their deep roots help prevent flooding by slowing water runoff, while their dense structure absorbs carbon, making them a valuable ally in the fight against climate change. A well-managed hedge isn’t just a scenic feature—it’s a working part of the farm, contributing to both productivity and environmental resilience.

Hedgerows for Everyone

Even for those who aren’t farmers or conservationists, hedgerows are an essential part of our shared landscape. They define the English countryside, offering a sense of continuity and belonging. Walking beside an old hedgerow, one can see its history woven into its structure—ancient oaks standing like sentinels, blackthorn and hawthorn twisting together, wildflowers bursting into life along its base.

These living barriers also play a key role in climate adaptation. They provide crucial shade in increasingly hot summers and form natural flood defences. With Devon (along with the rest of the UK) continuing to experience wetter winters, natural flood management has become a crucial part of our way of living. Hedgerows help slow the movement of water across the land, reducing the risk of flash floods and soil erosion. For communities, they are a space of quiet refuge, connecting people with the natural world in a way that tarmac and fences never could.

Our Experience - Digg & Co. in the Thicket

In February, Digg & Co. team members took part in a hedge-laying session, working together to revive a tired stretch of hedge. As the stems were cut and laid, the hedge was given new life—thicker, stronger, and ready to flourish in the coming spring.

There’s something deeply satisfying about working with the land in such a hands-on way, using traditional tools and time-worn techniques to restore something that will outlive us all. As we warmed our hands on mugs of hot oxtail soup, pricked by blackthorn and warming up by the fire, the experience reminded us how vital this practice is—not just for the landscape, but for us as a team. It reinforced our commitment to thoughtful, sustainable landscape design—one that honours these living structures rather than replacing them.

Each time we take part, our understanding of the land deepens. With every cut and lay, we’re not only strengthening our skill set but also strengthening our connection to the countryside itself.

Keeping the Craft Alive

Despite its many benefits, hedge-laying is at risk of fading into obscurity. The decline of traditional countryside skills and the push for mechanised farming have left many hedgerows neglected or lost altogether. But hope remains. Training schemes, volunteer groups, and organisations like the National Hedgelaying Society are working hard to keep this craft alive.

For those interested, there are plenty of ways to get involved. Landowners can invest in hedge-laying for their farms, while volunteers can join conservation groups dedicated to hedge restoration. Even supporting farmers and land managers who maintain hedgerows can make a difference.

Hedgerows are more than just boundaries; they are lifelines, histories woven into the land, and guardians of nature’s balance. To lay a hedge is to stitch together past and future, ensuring that these vital corridors remain for generations to come.

At Digg & Co., we believe that landscape design should work with nature, not against it. Hedgelaying is a perfect example of how human hands can enhance the natural world rather than diminish it. By keeping this tradition alive, we not only strengthen our countryside but also deepen our connection to the land we and other species call home.

So next time you pass an ancient hedge, take a moment to look closer. There’s more life woven into those twisted branches than meets the eye.

Unveiling Spring’s Subtle Heralds in Mid Devon

As winter's grasp loosens, the countryside around us awakens with understated signs of spring. Beyond the familiar daffodils and blackbirds, a closer look reveals nature’s more subtle cues of the season’s return. These overlooked signs—small, unassuming, yet deeply rooted in history and folklore—whisper their presence to those who take the time to notice.

One of the earliest botanical indicators of spring in the region is dog’s mercury (Mercurialis perennis), a humble green plant that flourishes in the dappled shade of ancient woodlands. Its name alone hints at its folklore—historically, it was believed to have associations with Mercury, the Roman god of communication and travel. Despite its delicate appearance, it is highly toxic to both humans and livestock, a trait that may have contributed to its mystical reputation. In the past, the presence of dog’s mercury was used to determine whether land had been continuously forested for centuries, making it a silent witness to Devon’s deep woodland history.

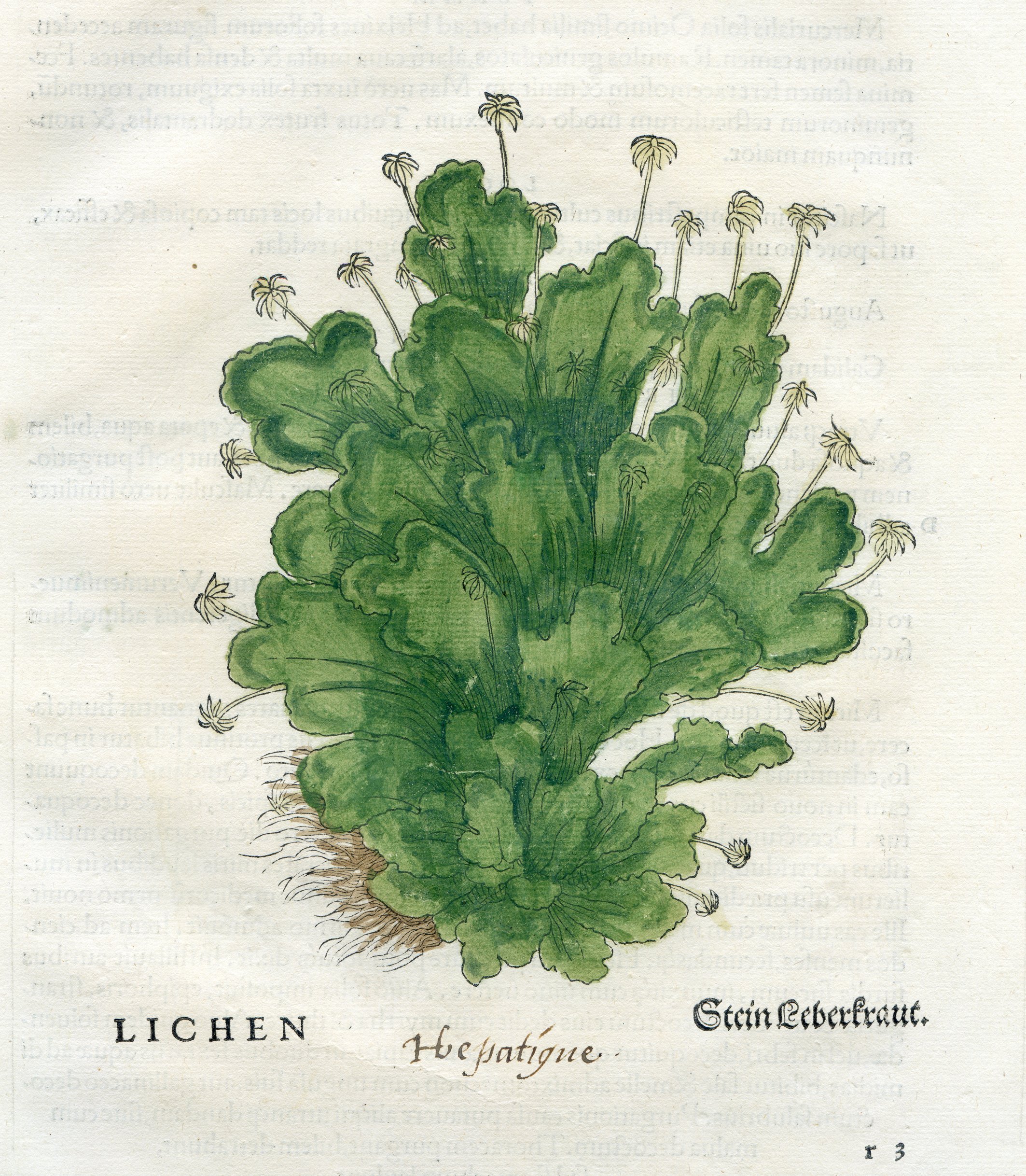

The unassuming yet ancient liverworts that cling to the damp stone walls and hedgerows of green lanes tell a different story. These primitive plants, some of the oldest life forms on Earth, have existed in one form or another for over 400 million years. Their presence is a quiet testament to the purity of the environment—these delicate organisms thrive only in clean, unpolluted air. In medieval times, liverworts were part of the Doctrine of Signatures, a belief system that held that a plant’s appearance indicated its medicinal use. Resembling a liver in texture and form, it was once used to treat liver ailments, though modern science has disproved its efficacy.

As the woodland edges stir with early birdsong, the song thrush (Turdus philomelos) begins to break the winter silence. Unlike its more boisterous cousin, the blackbird, the song thrush’s melody is intricate and repetitive, as if refining its song for the season ahead. In Victorian times, it was widely believed that thrushes could foretell the weather—if their song was particularly insistent, it was said to herald a coming storm. These birds also hold a place in British literature and poetry, notably inspiring the works of Thomas Hardy and Robert Browning, who admired the thrush’s defiant song as a symbol of hope and renewal.

Hidden within the cool waters of ponds and slow-moving streams, frogspawn makes its quiet appearance in early spring. This gelatinous mass of developing life has long been regarded as a symbol of fertility and transformation. In Celtic folklore, frogs were associated with the element of water and were believed to bring rain, making them an important figure in agricultural traditions. Their sudden appearance in spring also marked the moment when the land, long barren from winter, began to teem with life once more. Today, the presence of frogspawn is an important ecological indicator, revealing the health of local waterways and the resilience of amphibian populations.

On the first warm afternoons of the year, the buff-tailed bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) queen can be seen sluggishly emerging from her winter dormancy. Unlike the honeybee, which maintains a colony year-round, the bumblebee’s life cycle begins anew each spring, with a lone queen seeking out nectar and a suitable nest. Bees have been revered in folklore for centuries, often seen as messengers between the physical and spiritual worlds. In ancient Britain, it was customary to whisper secrets to bees, believing that they carried messages to the gods. The sight of a queen bumblebee searching for a nest is a small but vital moment in the renewal of life, as she will give rise to an entire colony of pollinators essential to the ecosystem.

On the woodland floor, the wood anemone (Anemone nemorosa) shyly unfolds its white petals, often before the trees above have fully leafed out. This delicate flower is steeped in legend—according to ancient Greek mythology, it was created from the tears of Aphrodite as she mourned the death of Adonis. In the British countryside, it is sometimes called the “windflower” because it was believed to bloom only when stirred by the breath of the wind spirits. Traditionally, it was thought to bring luck if picked before noon, though, in reality, its brief bloom is best admired in situ, as it is a key nectar source for early pollinators.

Meanwhile, Devon’s verges and stream banks become dotted with the glossy yellow flowers of lesser celandine (Ficaria verna). The poet William Wordsworth, so captivated by its bright, star-like blooms, wrote three separate poems dedicated to the flower. In folk medicine, lesser celandine was once used to treat scurvy due to its high vitamin C content, and its roots, resembling small tubers, were believed to cure haemorrhoids—hence its old name, “pilewort.” Though dismissed by modern medicine, it remains one of the first flowers to bloom in spring, its golden petals reflecting the increasing daylight and the quiet return of warmth to the land.

These overlooked signs of spring may lack the grandeur of daffodils or the fanfare of cuckoos, but they each tell a rich, storied tale of nature’s awakening. They are remnants of ancient landscapes, bearers of folklore, and silent heralds of renewal. By pausing to notice them, we gain a deeper appreciation for the quiet, intricate symphony of spring’s arrival.

Singing Fields - Why Sound Matters in a Thriving Landscape

As the winter frost recedes and the first signs of spring emerge, the landscape at Mill Barton comes alive with the unmistakable chorus of birdsong. After months of quiet, the air is filled with the melodies of nature—proof that the land is stirring and that a new cycle of life is beginning. At Mill Barton, we take pride in the relationship between the land and the birds that call it home, the Red Devons that help maintain it, understanding that their song and presence is a direct reflection of the health of our environment.

The return of birdsong to our fields is one of the most joyous signs of the changing season. The first notes we hear are often those of the Snipe, its drumming call echoing over the damp meadows, a sure sign that spring is on the way. As the days grow longer, the Skylarks rise into the sky, their song pouring from high above the earth like a cascade of notes. The robins, tits, and blackbirds join in, each with their distinctive tune, creating a symphony that resonates throughout the hedgerows and fields.

Among these familiar voices, the delicate warbles of the Garden Warbler and Blackcap begin to emerge, filling the thickets and woodland edges with their fluid, melodious songs. The Chiffchaff’s repetitive, cheerful call is one of the most unmistakable sounds of early spring, a persistent reminder that the seasons are shifting. Soon, the Willow Warbler joins in, its descending, wistful notes carrying on the breeze, a sound that epitomises the gentle unfolding of spring.

But perhaps the most eagerly awaited call of all is that of the Cuckoo. Its distinctive, echoing song announces its return from Africa, a sound that has signified the arrival of spring for generations. The Cuckoo’s presence is fleeting, yet its call is deeply embedded in the rhythm of the countryside, a timeless marker of the season’s renewal.

Soaring Skylark on the farm, April 2024

Following swiftly are the Swifts and Swallows. These birds, who travel thousands of miles to return to our farm, bring with them the promise of warmer days and longer evenings. Their aerial displays and joyful chatter are a reminder of the incredible migration journeys they undertake and of the delicate balance of the natural world.

The chorus of birds that greets us each spring is not an accident; it’s a reflection of the careful stewardship we practise here on the farm. The birdsong we hear each day is directly tied to the way we manage the land. Unlike intensively farmed landscapes, where the focus is on maximising output at the expense of biodiversity, we’ve chosen a path that prioritises ecological balance.

One of the ways we do this is by maintaining species-rich hay meadows, which provide food and habitat for a wide range of wildlife, including birds. These meadows are not fertilised with artificial chemicals or treated with pesticides, meaning they remain full of the wildflowers and grasses that birds depend on. Skylarks and other ground-nesting species find shelter here, while insects and other small creatures thrive, ensuring a healthy food chain.

The hedgerows, too, are an essential part of the landscape. These corridors of nature act as vital refuges for nesting birds and insects, and they play a crucial role in supporting biodiversity. By allowing our hedgerows to grow freely and only cutting them when necessary, we ensure that they remain full of berries, seeds, and shelter for birds like Robins, Blackbirds, and Tits. The insects that buzz through the grasses and flutter through the hedgerows also provide an essential food source for the next generation of birds.

Our Red Devons, roaming across the meadows, play an equally important role in this delicate balance. These cattle are not just part of the landscape—they help shape it. Their grazing patterns create varied sward heights, which in turn allow different plant species to thrive, creating the perfect conditions for birds and insects alike. The careful management of our cattle ensures that the land remains healthy and diverse, providing a foundation for both wildlife and farming to coexist harmoniously. The Red Devons, with their calm temperament and low-impact grazing, work alongside the land and the birds to foster a thriving ecosystem.

Our farming practices may seem different from the typical agricultural model, but they are rooted in a deep understanding of how nature works. Birds, cattle, and the land work in harmony. The birds help control pests by feeding on insects, while also contributing to the health of the soil through their droppings, which fertilise the earth. The Red Devons, in turn, support biodiversity through their grazing, which helps maintain the open spaces and diverse plant life that the birds rely on.

By allowing the land to rest and recover, we encourage this natural collaboration. Fields left to grow long and wild support more wildlife, while our decision to avoid intensive farming allows the soil to retain its vitality and its ability to nurture life. This partnership between birds, livestock, plants, and soil forms the foundation of a healthy, sustainable farm, where nature’s cycles are allowed to unfold without interference.

As we start to see the first few flutters of spring, we’re reminded that a healthy landscape isn’t just seen—it’s heard. The return of birdsong signals that the land is thriving, that our efforts to preserve the balance between nature, birds, and livestock are paying off. Each bird call, from the first Robin of the year to the distant song of a Skylark, is a testament to the success of farming that prioritises biodiversity, patience, and care.

For us, the sounds of the farm are as much a part of the landscape as the fields themselves. As we listen to the chorus of birds that fills the air, we feel a deep connection to the land and to the creatures with whom we share it. And as the Swallows and Swifts return to, we know that our work is helping to create a space where nature can thrive— and where the sound of life will resound through the fields, echoing across the land for years to come.

From Meadow to Plate - The Power of Species-Rich Hay

At Mill Barton, our cows are more than just livestock—they are an integral part of our farm, our landscape, and our philosophy. We take immense pride in stewarding them with care, ensuring they live healthy, contented lives while contributing to a thriving, biodiverse environment. A key part of this approach is feeding them species-rich hay.

Species-rich hay is a diverse mix of grasses, legumes, wildflowers, and herbs that have grown naturally in meadows, rather than the monoculture ryegrass often found in conventional livestock feed. These meadows are brimming with plant life—red clover, yarrow, self-heal, bird’s-foot trefoil, and crested dog’s-tail grass, to name just a few. Unlike intensively farmed pastures, which focus on a single species of fast-growing grass, species-rich meadows create a balanced and nutritious diet for grazing animals. They also support essential pollinators, improve soil health, and help store carbon in the land.

A cow’s diet directly affects its well-being, which in turn impacts the nutritional quality of the meat it produces. Feeding cows a varied, natural diet has several key benefits. Cows evolved to eat a diverse range of plants, and a mixed diet supports their digestive system far better than a diet dominated by a single species of grass or processed feeds. Meat from cows fed on species-rich hay tends to have a healthier balance of omega-3 fatty acids and is richer in vitamins and antioxidants. When cows eat a balanced, natural diet, they stay healthier, reducing the need for supplements, antibiotics, or grain-based feeds.

Many scientific studies have compared the crucial ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids in grass-fed versus grain-fed beef. In all cases, the omega-3 to omega-6 ratio in grass-fed beef was found to be better than the recommended level of 4:1, while most grain-fed beef exceeded this level. Sixty per cent of the fatty acids found in grass are the omega-3 fatty acid Alpha-Linolenic Acid (ALA), which is formed in green leaves. When cattle are taken off grass and fed a grain-rich diet, they lose their valuable store of ALA and other beneficial fatty acids. In 2011, the British Journal of Nutrition published a study concluding that eating moderate amounts of grass-fed meat for just four weeks would give consumers healthier levels of these essential fats.

Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), another type of fatty acid, has significant antioxidant properties and may be one of the most potent defences against heart disease, diabetes, and cancer. Beef is one of the best dietary sources of CLA, and 100% grass-fed beef contains significantly more of it than beef from grain-fed animals. Additionally, meat from fully grass-fed animals contains considerably more antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals such as beta-carotene and vitamin E than meat from grain-fed livestock.

The terms 'grass-fed' and 'pasture-fed' are often used interchangeably, but they are not the same. Under Defra rules, an animal only needs to have 51% of its diet based on grass to be labelled as grass-fed. In many cases, grass-fed systems still include significant amounts of concentrated feeds like barley and soya to speed up growth. In contrast, Pasture for Life producers ensure that animals eat only grass, herbs, and forage (including hay, silage, and lucerne) for their entire lives. This means no grain, no unnecessary concentrates—just a natural, species-rich diet.

There’s a well-known saying: you are what you eat. But it goes deeper than that—you are also what your food eats. When we eat meat from cows that have grazed on species-rich pastures, we are consuming the benefits of that diverse, natural diet. The nutrients, healthy fats, and minerals that the cows take in are passed along to us. In contrast, meat from intensively farmed animals raised on grain or processed feed often lacks the same nutritional profile. The same principle applies to environmental health. Cows that graze on species-rich hay help maintain meadow habitats, improve soil structure, and encourage biodiversity. This means that choosing ethically raised, pasture-fed meat isn’t just about taste and nutrition—it’s about supporting a healthier, more sustainable food system.

The impact of species-rich hay goes beyond the cows—it supports an entire ecosystem of wildlife. Traditional hay meadows are home to an incredible array of birds, insects, and small mammals. Skylarks, barn owls, and lapwings thrive in these open landscapes, while pollinators like bees and butterflies benefit from the diverse flora. By maintaining these biodiverse pastures, we also encourage the growth of native plant species, many of which are in decline due to intensive farming. Wildflowers such as devil’s-bit scabious, betony, ragged-robin, and meadowsweet not only add beauty to the fields but also play a crucial role in soil health and supporting insects that contribute to natural pest control. Restoring and protecting these meadows ensures that farming and nature can thrive together, rather than being in conflict.

Britain’s countryside was once rich with traditional hay meadows, but over 97% of them have been lost since the 1930s. By supporting farms that prioritise species-rich pastures, we help to reverse this trend, bringing back biodiversity and restoring soil health.

At Mill Barton, we see our cows as part of a bigger picture—one that connects ethical farming, landscape management, and great food. When you choose to eat meat from animals raised on species-rich hay, you are making a conscious decision to support better farming, healthier animals, and a more balanced countryside.

Where Rivers Run Wild Again: The Art of River Restoration

Introduction to River Restoration

River restoration is a process that seeks to return rivers and streams to a more natural and functional state, addressing the damage caused by centuries of human activity. Many rivers in the UK have been straightened, polluted, or obstructed, leading to issues such as increased flooding, reduced water quality, and a loss of biodiversity. In response, a variety of restoration strategies are employed to improve these vital ecosystems.

These strategies include removing artificial barriers, reintroducing natural meanders, and enhancing habitats for wildlife. While it’s often not possible to fully restore rivers to their original condition due to irreversible changes in the landscape and human dependence on water resources, rivers are resilient and capable of recovery when given the right support. Restoration efforts focus on aiding this recovery by addressing hydrological, morphological, biological, chemical, and societal challenges within the catchment area.

The aim is not only to improve ecological health but also to create more resilient landscapes and cleaner water systems. Restoring features such as migration routes for fish such as salmon or reintroducing native vegetation along riverbanks which enhances biodiversity and helps to restore natural river processes. River restoration goes beyond ecology—it is about preserving the beauty, function, and sustainability of our waterways, ensuring they can thrive for future generations.

Re-meandering and Brash Dams: Reviving Natural River Dynamics

One of the most effective techniques in river restoration is re-meandering, which involves reintroducing the natural curves and bends that rivers often lose due to human intervention. Straightened rivers may seem more efficient, but they disrupt the flow dynamics, increase erosion, and reduce habitats for aquatic and riparian species. By restoring these meanders, rivers slow down, allowing sediment to settle naturally, reducing flood risks downstream, and creating varied habitats for fish, insects, and plants.

Natural Flood Management (NFM)

NFM is an innovative approach that uses the power of nature to reduce the risk of flooding and improve the resilience of landscapes. Also referred to as Natural Water Retention Measures (NWRM) or Nature-based Catchment Management (NbCM), NFM focuses on restoring or mimicking the natural processes that once governed rivers, floodplains, and the surrounding environment. By allowing rivers to function more like they did before human interventions, NFM helps slow the flow of water, which can significantly reduce flood risk downstream. But it does more than that—by enhancing the ability of the landscape to retain water, it also helps to make land more resilient to drought conditions by releasing water more slowly over time.

NFM involves a variety of techniques designed to work with nature, rather than against it. For example, leaky dams—constructed from wood, stone, or other natural materials—are placed in streams to slow water down and allow it to spread out, reducing the speed and volume of water downstream. Swales, which are shallow, vegetated ditches, can be used to capture rainwater and direct it away from vulnerable areas, while offline ponds hold water temporarily during heavy rainfall, preventing it from overwhelming the river. Remeandering rivers helps restore natural curves, allowing water to slow down and spread out rather than rushing in a straight line. In addition, land management practices such as controlled grazing, reforesting, and planting cover crops improve soil health, making it more absorbent and reducing surface runoff. Soil management also plays a key role by improving infiltration and reducing erosion. Finally, the reintroduction of beavers can play a vital part in flood management, as their dam-building activities naturally slow water and create wetland habitats, which help retain water and reduce flood peaks.

Alongside re-meandering, smaller interventions like brash dams play a crucial role. These simple structures, made from natural materials like branches and twigs, are placed across the river or its tributaries. Brash dams mimic natural woody debris, slowing water flow, trapping sediment, and creating pools and riffles. These features are vital for aquatic life, offering spawning grounds for fish and habitats for invertebrates.

Stourhead Estate and Panford Beck

In our recent projects at Stourhead Estate in Wiltshire and along Panford Beck in Norfolk, we've successfully implemented some of these techniques to restore natural river dynamics.

Stourhead Estate Masterplan

At Stourhead Estate, renowned for its 18th-century landscape gardens, the original design included the creation of a large artificial lake by damming the River Stour. Over time, sediment accumulation and changes in water flow necessitated restoration efforts to maintain the lake's health and aesthetic appeal. By reintroducing techniques as above, we've helped to enhance water quality, reduced sediment build-up, and revitalised habitats for local wildlife.

Similarly, at Panford Beck, a tributary of the River Wensum in Norfolk, we've applied these restoration techniques to great effect. These interventions have also contributed to better flood management, helping the return of native species and increased resilience of the local ecosystem.

These projects demonstrate how combining traditional landscape aesthetics with modern ecological restoration techniques can yield benefits for both heritage sites and natural environments.

What is Stage 0 Restoration?

Stage 0 restoration is a cutting-edge approach to river restoration that aims to reset a waterway to its most natural, undisturbed state. Unlike traditional restoration methods, which often involve specific interventions such as remeandering or installing brash dams, Stage 0 focuses on reconnecting a river with its original floodplain and allowing it to flow freely across the landscape. This process often involves removing artificial barriers, drainage ditches, and embankments, essentially giving the river permission to behave as it would have before human interference.

A prime example of Stage 0 restoration in the UK is the National Trust’s Holnicote Estate project on Exmoor. This groundbreaking initiative has transformed the waterways of the estate by completely rewilding sections of the river. Instead of following a straightened course or even a carefully engineered meander, the rivers at Holnicote are now allowed to spread, braid, and create their own paths across the floodplain.

The results have been remarkable. Flood risks downstream have decreased as water is naturally slowed and absorbed across the landscape. Sediments are deposited where they would have been historically, improving soil health and reducing silting in downstream rivers. Wildlife has flourished too, with wetland habitats returning to support species like otters, water voles, and wading birds. The benefits aren’t just ecological; local communities benefit from improved water quality, reduced flooding, and a restored landscape that’s more resilient to climate change.

Stream evolution model (Cluer and Thorne 2013). Stage descriptions are provided in Table 5. Dashed arrows indicate "short circuits" in the normal progression.

A Ripple Effect